At the heart of the Estate lies a walled garden, basking on a south-facing slope and protected from the wind on all sides. Inside it you’ll find our greatest treasure: an espaliered apple-tree maze.

The maze is laid out on a series of descending terraces in the formal, ornate style of the Baroque. Welcome to the year 1688, when William and Mary came, jointly, to the British throne. Theirs might have been a political match, but this royal husband-and-wife team enjoyed a famously harmonious and affectionate marriage – his Dutch reasonableness combining well with her English gentleness and sense of fun. Not only did they pave the way for parliamentary democracy during their time as rulers, but they modeled for the nation a shared passion for gardens and a horticultural expertise to go with it.

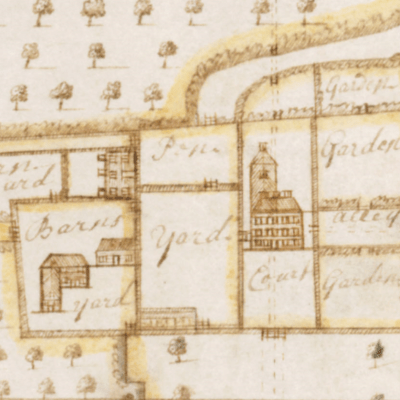

The wall of this garden is unusual in that it traces the curved line of a parabola – or half an egg. This egg shape led the garden’s designer, Patrice Taravella (the man also responsible for the eight-acre potager at Babylonstoren in South Africa) to his idea of an apple maze, reminding him as it did of the Latin phrase “Ab ovo usque ad malus”. Literally translated, this means “From the egg to the apple” but it is metaphorically closer to the English phrase "From soup to nuts”, or a meal with all its courses. And so, starting at the egg, he arrived at the apple, a sense of completeness, and William and Mary – the two halves that make a whole.

If you grew up in an apple-growing region in the UK, you might want to find your county – because, be it Cornwall or Cumbria, London or Lancashire, each apple county has its corner in this maze. Once you’ve located your county, take a look at some of the labels on the trees: there’s nothing like a poetic apple name for transporting you back to your childhood, particularly when you can smell that apple, too. If you’re from Somerset or Kent, you’re in luck: these two great apple counties get an archway all to themselves, with each pair of trees joining hands above your head so that you can pass beneath, like a dancer in a country dance. All the apple varieties growing here were being cultivated in Britain by the year 1688, and could have been picked by William for Mary – or indeed by Mary for William.

At the time this protestant pair arrived from Holland to knock Mary’s Catholic father, James II, off the throne – bloodlessly, it should be added – Europe was still reverberating from the extraordinary creation of another Catholic king. Across the channel, Louis XIV of France had built Versailles, setting a whole new standard for the scale, splendour and spectacle of royal gardens. At once, vast formal gardens that celebrated man’s dominion over nature began springing up around Europe as princes and dukes sought to emulate Versailles. Broad avenues radiated out from grand houses, inviting visitors to extend their gaze into the surrounding countryside. Magnificent parterres de broderie, made of box, were rolled out in scrolls and arabesques. Impressive water features, topiary and classical statuary were installed to punctuate and amaze. Peterhof in Russia, with its grand central cascade and 64 fountains was created at this time; as well as Herrenhausen in Germany, with its giant parterre covering an extraordinary 50 hectares. And in the Dutch Republic, another elite couple, William of Orange and his English wife Mary avidly studied the panoramic paintings being made of Versailles and copied the swirling baroque lines of the parterres around their hunting lodge, Het Loo.

When they inherited Hampton Court in England, where Charles II – Louis XIV’s cousin – had already dug the hugely ambitious three-quarter-mile Long Water Canal, they brought their expertise with them. They added the splendid fountain garden and the famous maze. They also planted many more flowers, especially tulips. Mary’s genuine interest in exotics from far-off lands was supported by William’s business savvy; and with the help of the Dutch East India Company, they imported unusual specimens from countries as far as Sri Lanka and Barbados. Thus the seeds were sown for the plant-collecting craze that would peak with the Victorians, nearly two centuries later.

An espaliered tree is a tree that has been trained to grow in a two-dimensional form – partly for the pleasing lines, but also to allow the ripening rays of the sun to reach the fruit more easily. The Romans were the first to train fruit trees in this way; but it was the French who elevated the practice to an art form. You can read more about the expert fingers of our espalier artist, Gilles Guillot, on the plaque(s) in this part of the garden. You’ll notice how the structural lines of the trees are picked up by the playful arcs and sweeps of the hedges as they journey downhill in the parabola garden, while the water, bubbling up from its source stone at the top of the garden, completes this sense of movement, flowing down its central rill and toppling over multiple cascades. The pebble mosaic(s) with its/their soft, river-rounded stones in gradually shifting shades of grey and white are our modern take on the Baroque’s passion for patterns, while the apple trees at the corners of the garden break out of the convention and venture into three-D to form domes, spirals and columns.

Baroque gardens were all about royalty, and this one is no exception. Towards the outer edges of the garden you’ll find our nod to the French royal family of the time in the form of Reinettes or ‘little queen’ dessert apples, such as ‘Reinette Dorée de Versailles’. And espaliered against the inside walls are a repeated pattern of French crab apples, with Malus ‘Jelly Kings’ flanked by Malus ‘Comtesse de Paris’. Just in case the countesses get too coquettish – or the Reinettes too jealous – we’ve planted Malus x rob ‘Red Sentinels’ to keep watch.

Mazes are places in which to lose ourselves – then re-discover ourselves again. They’re also places for trysts and assignations. If you come in spring, the apple maze will be at its most seductive, resplendent with apple blossom. In summer, you’ll be able to spot the shy fruit taking shape amongst the branches. In the autumn, just before the apples are harvested, the scent of the fruit will be at its most heady. And in winter, you’ll be able to appreciate the bare, silhouetted lines of the espaliered trees as they wait, holding their breath, for the short days and sharp frosts to pass.

You’ll sometimes find apples bobbing in the central water basin, or placed in a basket by gardener Andy 'Apples' Lewis. Help yourself – washing your apple first under the drinking-water tap. Perhaps today, like William and Mary, you too will find a sense of completeness, the other half that makes you whole.